“If we win, we’ll come to the wrong evaluation of the factors that determine victory. If we lose, the reasons are always very clear. Every time we lose, we learn how to build new cars.” – Enzo Ferrari.

“If we win, we’ll come to the wrong evaluation of the factors that determine victory. If we lose, the reasons are always very clear. Every time we lose, we learn how to build new cars.” – Enzo Ferrari.

What were the lessons to learn from RWC 2019 for Andy Farrell and the group that has become his Irish squad?

How to identify the salient lessons from a loss, and how to divorce painful emotions from the logical reasons behind failure are difficult tasks. The personnel who may have the most in-depth knowledge of a given situation may not be best placed to assess it rationally due to emotional attachment, unrelieved bias or lack of perspective. Those on the outside looking in have an advantage in terms of an overview, but it’s difficult to avoid the suspicion that analysis is flavoured to suit preconceptions – think how rarely you’re surprised by a particular journalist’s take on a situation – and that a huge amount of detail [like injury niggles, dissatisfaction with selection, arguments over tactics, fallings-out and training-pitch bust-ups, tension and stress in build-ups, satisfaction or frustration after matches] is concealed or ignored for reasons that vary from the unthinking to the necessary to the needless to the petty.

Of course, there is no one truth; everybody’s ‘truth’ is shaped by their own experience and perception of a given situation. Any analysis of Ireland’s World Cup campaign will show gaps in knowledge and come up with contentious appraisals, but that doesn’t mean that it is not worth taking on. If nothing else, it is always enlightening to come back after a significant period of time – after the narratives have coagulated and latter events have mysteriously been brought to bear on a story that ended long before – and read back on your opinion at a time when your attention was entirely focused on the tournament, and the communal history [the groupthink, to consider it pejoratively] of the event hadn’t yet been established.

Janus

In the Roman pantheon, Janus was the god associated with beginnings, transitions and endings; his two-faced representation reflected his ability to see into the past and the future.

This series of articles was undertaken at a time when The Mole was trying to play Janus: looking backwards to the last tournament, the Rugby World Cup in 2019, and forwards to the next tournament, the 2020 Six Nations. What now seem [with glorious twenny-twenny heinzight] to have been trivial events conspired against timely publishing, but the advent of the Covid-19 lockdown has given a second lease of life to the series now that the sound of barrel-scraping is audible across the sporting press.

2019 was a staggeringly disappointing year for Irish rugby, primarily because 2018 had been so successful and seen such euphoria. Still, the Irish rugby public’s appetite for World Cup recrimination was more or less sated about six weeks after the tournament had ended. This wasn’t the mystery of 2007, when a hyper-confident team that had thrived in the preceding Six Nations turned up in France as flat as a pancake; the loss of form of the 2019 team had unfolded over nine months, and while the reasons for it were still puzzling, we had all got used to the idea that the team had peaked and was on its way down the other side of Mount Form [2018m]. The calamitous loss against New Zealand wasn’t a bolt out of the blue. It was just as bad as Irish fans feared it might be.

While there’s no widespread desire to break through the scum on the surface and swill a bare hand through the murk of Ireland’s unsuccessful attempt to win the William Webb Ellis trophy in Japan in order to feel out a few pearls of wisdom, it’s a worthwhile exercise to undertake now. Passions have cooled and the sting of disappointment is less sharp.

The analysis will focus largely on players’ performances in RWC19, with asides on different squad selections. It uses four squads as a narrative frame: the last two squads of Joe Schmidt’s tenure [the big May 2019 training squad and the small September 2019 tournament squad], and the first two squads under Andy Farrell [the large ‘stocktake’ squad of December 2019 and the small January 2020 tournament squad].

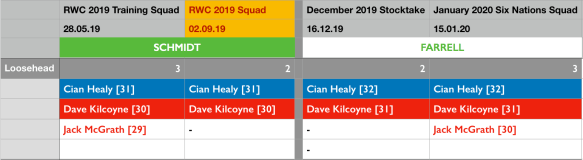

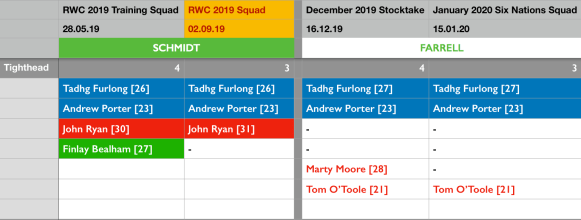

The front rowers selected in the last four Irish squads; Schmidt selected the squads in columns one and two, Farrell the squads in columns three and four. The date of each squad announcement is indicated below the squad name. Each player is represented in his provincial colour, with his age at the time of the squad announcement in square brackets alongside. The double-dagger [or diesis, ‡] indicates an injured player, and a +(player) indicates a player called into the squad as a replacement.

Loosehead

Going into RWC19, Ireland’s loosehead depth was enviable: three experienced test players in the primes of their respective propping careers, with one of them clearly in the best form of his life.

The looseheads selected in the last four Irish squads; Schmidt selected the squads in columns one and two, Farrell the squads in columns three and four. The date of each squad announcement is indicated below the squad name. Each player is represented in his provincial colour, with his age at the time of the squad announcement in square brackets alongside. The double-dagger [or diesis, ‡] indicates an injured player, and a +(player) indicates a player called into the squad as a replacement.

Healy’s renaissance started on the June 2017 tour to Japan. Jack McGrath was Ireland’s starting loosehead throughout the 2016-17 season [and had been for much of the previous two seasons] and the St Marys man’s selection for the Lions tour to New Zealand meant that Healy got a chance in the green No1 jersey. He performed excellently on tour and hasn’t let the jersey go since.

- Squads: 4 [May 2019, Sep 2019, Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 32

- RWC19 Games: 4

- RWC19 Starts: 4

- RWC19 Minutes: 201

Healy turned 32 during the World Cup. This is his eleventh season of test rugby, his third World Cup, and it seems like he should be older. His test career started as far back as Declan Kidney’s second year in charge, which seems like a long time ago at this point of recollection. He made his debut against Australia in November 2009; he was essentially parachuted into the 2009 Grand Slam winning team.

Going on the evidence of this tournament, he has some good years ahead of him. His workrate was high, his set-piece work rigorous, his error count low, and his discipline was creditable throughout the tournament. In a squad full of experienced players whose performances staggered at crucial stages, he held the line with a minimum of fuss.

The loosehead selection worked smoothly for Ireland – the best of any position – and threw up no unexpected injuries, dips in performance or disciplinary issues. Two experienced players accounted for the vast majority of gametime [378 of a possible 400 mins], and the remainder was picked up, as intended, by the youngest prop in the squad.

Healy and Kilcoyne split their gametime equitably [53% going to Healy, 47% to Kilcoyne], and in broad terms both players delivered what they were asked to do. They are a complementary pair stylistically, which is more of a nuance than a factor now that most sides change their props over roughly the same 10-minute period; it’s not as beneficial as it used to be in the days of a seven man bench, when a prop designated to go the full 80 minutes might have to deal with two very different scrummaging approaches. However, the effect is still there in how the two Irish looseheads perform in open play; they each give a different look and pose different problems to the opposition with their distinctive traits. Healy favours late footwork when he carries, whereas Kilcoyne explodes in a straight line. On the other side of the ball, the Clontarf man is an excellent technical tackler with the ability to drop his hips late and power upwards, while Kilcoyne … explodes in a straight line!

In term of a statistical analysis, there was very little difference in what they delivered in open play over the tournament: RugbyPass has Healy carrying 18 times for 27m [1.5m/carry] and Kilcoyne with 25 carries for 28m [1.1m/carry]; without the ball, Healy went 18/1 in terms of tackle count, Kilcoyne 18/2.

However, the point that all the loose work is a secondary concern to the tight work was hammered home by the scrummaging contest in the final. It was fascinating to see Tendai ‘The Beast’ Mtawarira lead the destruction of the English eight over the course of the World Cup final. You can sometimes forget how dangerous a powerful scrum can be, and how important it is to maintain a solid scrum on your own ball; as spectators, you can begin to take an unyielding set-piece for granted.

The scrum is a unit skill, and Healy’s efforts at loosehead were just one part of its general success. Over the course of the tournament, Ireland gave little away on their own ball and lost just two scrums against the head: one against Japan, and one against Samoa. Furlong struggled against Japan – even though World Rugby came out and said he was incorrectly penalised, he still struggled – but Healy took care of his end from gun to tape.

Kilcoyne only made one start during the tournament [against Russia, above], but he made an impact every time he took the pitch. His introduction against Japan was especially noteworthy. Ireland had really begun to tire and were soaking all across the pitch, but Kilcoyne raced off the defensive line twice in quick succession to deliver enormous collisions and it bucked up his teammates’ ideas. It came to no avail, but they were still great plays.

- Squads: 4 [May 2019, Sep 2019, Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 31

- RWC19 Games: 5

- RWC19 Starts: 1

- RWC19 Minutes: 177

Dave Kilcoyne was a conspicuous success at the World Cup, giving frequent evidence that he’d packed the form that had got him on the plane. His explosive carrying ability has always been his point of difference, but in the past he wasn’t fit enough to make dynamic repeat efforts. An off-season re-determination of his training and dietary regime saw him enter the 2018-19 season considerably leaner and stronger than he had finished the previous term … and to his credit, he has managed to maintain that drive for well over a year. Kilcoyne overtook Jack McGrath’s spot on the Irish bench in time for the 2019 Six Nations, but didn’t stop to admire the view. He just kept on getting better.

The areas where Kilcoyne improved this season – aerobic fitness, tactical knowledge, discipline at scrum-time – all bear the hallmarks of a mature player, and a player who has become more coachable as he has got older. Three or four years ago, what looked like the results of an inconstant approach to aerobic conditioning and a disregard for coaching would frequently catch up with him on the pitch. Kilcoyne’s modus operandi at the time stemmed around making a charge on to the ball, being the last man off the floor and then standing around in the backline until he got his wind back. The Mole particularly remembers the Pro12 final against Glasgow in 2015, when a puffed Kilcoyne would take plays off after carries and find himself first stranded, then rounded when the Scots counter-attacked.

The legendary Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi used to say that fatigue makes cowards of the strongest men. Most people involved in sports have heard that by now, but it’s one of those clichés that hasn’t lost its bite. Nobody likes being called a coward. But anybody who has played recognises the feeling when you’re at the extremes of your fitness and you – essentially – just give up. You quit. You let your opponent get one up on you, you give up a chase … whatever. You quit because you’re exhausted.

Kilcoyne’s former approach to professional preparation occasionally resulted in his mouth outrunning his legs. His vastly improved fitness and habits in recent times have allowed him to reach his playing potential, and then stay at that high performance level for months and months on end. It has been a very significant improvement on his previously one-dimensional method: when he’s fit, he can hit his go-to strengths more often … but he can also concentrate longer, stay in the fight longer. That has resulted in fewer penalties, fewer missed tackles, fewer botched alignments and the best season of his career.

McGrath cuts a frustrated figure during the humiliating 57-15 loss against England in August 2019. Having played in 31 [21+10] of Ireland’s 44 tests since the 2015 quarter final – and missing three of those in the summer of 2017 only because of his selection for the Lions – his omission from the squad for RWC19 would have been unthinkable at any stage in 2018.

- Squads: 2 [May 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 30

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC19 Starts: –

- RWC19 Minutes: –

Jack McGrath played almost half an hour of the November 2018 win over New Zealand, a fact that tends to be overlooked when assessing his form through the 2018-19 season. The Lions tourist had to have surgery on a hip injury the following month, and his season stalled and then lost altitude with a stomach-clenching abruptness.

The Mole remembers a big deal being made of the fact that Ed Byrne was preferred to McGrath as back-up loosehead for Leinster’s home fixture against Toulouse in early January 2019. It seemed like a completely rational selection to me: McGrath had only played one game for Leinster in the ten weeks since the end of October, whereas Byrne had featured in six of the seven games over that period. McGrath started the next week in the final game of the group stages, a facile 19-37 win over Wasps in Coventry.

However others were quicker to read the writing on the wall than The Mole [I’m famously myopic], and the writing said that McGrath was on the way out and Kilcoyne was coming in through the front door.

McGrath had finished the 2016-17 season as one of the four or five best looseheads in the world and toured with the Lions that summer, featuring off the bench in all three tests and averaging about 22 mins/match in those hard fought encounters. He was a little unlucky not to have got a start in at least one of those games: Mako Vunipola’s star wasn’t as high in the sky as it was in 2019, and his discipline was atrocious in the test series. In the end, McGrath only made one start in seven games. He featured in all the big ones – against the Crusaders, the Maori and those three test matches – but his only start came at the front end of the tour, against the Auckland Blues.

McGrath wouldn’t be the first player to suffer a post-Lions slump in form. However, rather than any horrific decline in his personal showings, it was Healy roaring back into form for both Ireland and Leinster while McGrath was away – first on the tour to Japan, then in the early stages of Leinster’s domestic season – that swung the brass ring away from the St Mary’s loosehead and back towards Clontarf’s prize bull.

While his grasp on the No1 jersey had slipped, McGrath still featured in every match of the 2018 Grand Slam campaign and started two of the three tests in the series win in Australia. He picked up a niggling knee injury in early September 2018 – an injury that saw him miss the first four games of the domestic season – and after the aforementioned New Zealand game he decided to have surgery on the hip complaint that he had carried throughout the 2017-18 season. Then one after another the struts gave way. First it was losing that selection call to Ed Byrne at Leinster, then Kilcoyne for Ireland. Shortly after the Six Nations – a Six Nations in which he played in just one game, having played in all 25 of Ireland’s games over the previous five editions of the tournament – he announced that he had signed for Ulster and would be joining them after the World Cup. That impacted negatively on his selection for Leinster games, and he was overlooked for three of Leinster’s four knock-out games in the aftermath of the announcement, only making a nineteen minute cameo appearance against Saracens in the European Cup final. That was the only game Leinster lost of the four. The Mole’s point isn’t that McGrath lost the Saracens game for them, it’s that he wasn’t missed in the other three. The coaching team weren’t sweating that the team would lose out based on what he could bring to the table. Ed Byrne was able to pick up the slack, averaging just under twenty minutes/game in two semi-finals and a final.

In the end, the RWC19 selection wasn’t even really a close call. Kilcoyne excelled during the scheduled warm-up fixtures in August and September, and McGrath was nowhere near his best.

Schmidt gave McGrath all 56 of the Irish caps he has won in his career to date. Leaving him at home may have been a straight-forward decision, but it can’t have been an easy one. The New Zealander was heavily criticised throughout 2019 – especially in the Irish rugby media – as having shown too much loyalty to favoured players. Ask McGrath, Devin Toner or Keiran Marmion about Schmidt’s loyalty and you’ll get a different answer.

In Summation: Looseheads

The fact that all three looseheads named in Farrell’s Six Nations squad are in their 30s would have the long-term planners amongst Irish rugby fans fretting about age profile in a World Cup cycle. I’m as much a believer in squad age profile as the next rugby guff-spouter, but The Mole will refrain for the moment from joining the reactionary call to cull all of Ireland’s 30-somethings and ‘sacrifice a Six Nations’ for the sake of … something. Progress? The brotherhood of man? While said age profile is far from ideal, The Mole isn’t sweating it quite yet.

I expect that the squad size will increase to 32 for the next World Cup, and that roughly half the coaches will opt to select a sixth prop, while the remaining half will opt for a sixth halfback. That will lead to further platooning of the scrummaging effort, while the emphasis that the champion Boks have put on their set-pieces, their early forward substitutions and their 6/2 bench split will also prove influential. The knock-on effects of that will likely be shorter playing times for all props, more rotation and probably extended playing careers.

Hooker

No position has shown more change than hooker. Of the three hookers whom Schmidt selected for Japan, none have made it to Farrell’s first tournament squad. The 37 year old Rory Best [124 caps] retired of his own volition; the 33 year old Sean Cronin [72 caps] was an early scratch, uninvited to the December get-together; and the then-27 year old Niall Scannell [20 caps] was an overtly surprising omission from the Six Nations squad.

It’s curious to look across the chart above and see Rob Herring as the constant. Herring has been peripheral to the Irish set-up since making his test debut in June 2014 on tour in Argentina, while Best and Cronin have been constants for over ten years, winning a combined 196 Irish caps.

Even given the fact that he looked in exceptionally good physical condition during the pre-season, Best is an awful lot closer to 40 than he is to 30. To see him go the full 80 minutes in the opener against Scotland was surprising. He’s 37 years old, for fuck’s sake!

Rory Best

- Squads: 2 [May 2019, Sep 2019]

- Age: 37

- RWC19 Games: 4

- RWC19: Starts: 4

- RWC19: Minutes: 255

Ireland’s captain had a worrying prelude to the RWC, with a dismal performance out of touch against the English the nadir. This mistake-ridden outing led to a distinct unease in the Irish rugby public regarding his captaincy, his viability as starting hooker, and even his place in the squad.

Best tipped the negativity on its head and delivered commendable performances throughout his fourth World Cup. The lineout, which had been not just a source, but an overflowing fountain of concern, functioned at an efficient level throughout; over the course of his four games, Ireland lost just two on Best’s throw – both of them on lineouts from penalties against the Brave Blossoms of Japan, unfortunately. Still, two lost throws over the course of four games is an excellent return. The lineout is a unit skill, so Best shouldn’t get all the credit, but he should get his due for taking care of his responsibilities.

§ Sidebar: A Love Letter To Shota Horie Masquerading As A Comparison With Best

Once you bear in mind that hooker is the one position in the pack that has to rely on fine motor skills in the same manner as the backs, then the deployment of your hooker as an auxiliary distributor and playmaker in attack makes perfect sense. Japanese hooker Shota Horie [the outstanding No2 in the tournament, to my mind] was the prime exponent of this arrangement in the tournament. He averaged more than 15 possessions/game in the four matches he started in the tournament [he didn’t start against Samoa], and his pass and offload percentage [P&O%] from those possessions averaged 38.5%. There were no outliers in his four starts; Horie’s P&O% always hovered around that figure.

- 12 possessions | 42% P&O vs. Russia

- 21 possessions | 33% P&O vs. Ireland

- 20 possessions | 35% P&O vs. Scotland

- 9 possessions | 44% P&O vs. South Africa

Best had an extremely high P&O% over his four starts: 53%. It would have been even higher had it not been for the up-the-jumper tactics against Samoa, which were appropriate for the man-down situation.

- 14 possessions | 71% P&O vs. Scotland

- 6 possessions | 50% P&O vs. Japan

- 6 possessions | 16% P&O vs. Samoa

- 8 possessions | 75% P&O vs. New Zealand

Some of Best’s passing, against New Zealand in particular, was exceptional – well disguised, well-flighted, and right at the point of contact. However, it’s immediately apparent from the figures above that Shotie’s role in midfield was pivotal, while Best’s was an addendum. Horie’s average number of possessions/game almost doubled Best’s [15.5 possessions/game to 8.5 possessions/game]. A small portion of that can be put down to time on the pitch: Horie averaged 74.5mins/game in the four games he started, while Best averaged 63.5mins/game. That still breaks down to a possession every 4.8mins for Horie and every 7.5mins for Best.

Of course, attack is only one part of the game. Horie’s efforts in defense, particularly in the games against Russia and Ireland, were heroic – 18/0 tackles made/missed in the former, and 17/1 in the latter. His outstanding fitness and reading of the game ensured that he was very frequently close to the ball, and he made an outstanding number of open-play actions [kicks + passes + runs +attempted tackles] in his starts in the pool, an average of 34/game. Best’s starts in the pool [vs Scotland, Japan and Samoa] yielded an average of 17/game.

Strategy and tactics come into play, as does time in opposition territory, but that’s a huge difference. It’s 2:1. Horie’s pack were frequently out-weighed in the scrum and always out-talled in the lineout [no, it’s not a word], but the Japanese pack coped brilliantly in the set pieces until they came up against the Bad Giants of South Africa. The Japanese hooker’s efforts in the set-piece were of the same standard as his work in open play. At 33 and a good bit, Horie is no spring chicken either … but he’s more than three years younger than Best and doesn’t have the same mileage as Ireland’s record-holding hooker.

… And We’re Back

The point of this long comparison is to iterate the fact that while Best’s role in the team had changed and become more advanced, the Japanese team were quite a way further up the ladder. Best has also come to the end of his term as a player, and Ireland have to move on. Hooker is a position that has always been recognised as forming part of the ‘spine’ of the team, but it is the increased role in open play [as evinced by Horie] that shows a potential – and logical – route for development of the position as part of a spine of decision-makers and play-makers.

Niall Scannell’s World Cup sort of passed him by. He wasn’t a surprise selection, especially with Herring’s early scratch. He isn’t a senior player who’ll have to carry the can for the rest of the season. He featured in a good few games without making any significant impact, and he kept his nose clean. There’s not an awful lot more to say.

Niall Scannell

- Squads: 3 [[May 2019, Sep 2019, Dec 2019]

- Age: 28

- RWC19 Games: 4

- RWC19 Starts: 1

- RWC19 Minutes: 110

Like his provincial colleague Kilcoyne, Scannell presented for the pre-tournament fixtures looking considerably leaner and better-conditioned than in previous seasons. It was immediately evident on the touchline when he replaced the unfortunate Rob Herring early in the Lansdowne Road match against Italy, and apparent even in his face: he looked less jowly, less puffy around the cheeks. The RWC tournament site listed him as 107kg, down some 4kg from his weigh-in on the Munster site. I’m not sure exactly how accurate that is, but it seems plausible. Bundee Aki put his own weight loss down to avoiding Super Macs; whatever it was for Scannell, it worked.

An account of his World Cup? Beige. He didn’t make any major impact, and he didn’t have any disasters. He wasn’t put in a position to do so. Six minutes as a flanker against a well-beaten Scotland; an average hour in a misfiring team against easy-beats Russia; half an hour of meat-grinder rugby [Der Fleischwolf] against a Samoan side who were already 5-33 down when he was introduced; and the last 17 minutes of a quarter-final that had been lost forty minutes before he stepped on the pitch. It’s not Roy of the Rovers stuff, but it’s not his fault either.

The Dolphin man is a full decade younger than Rory Best, and is well-placed to profit from the Ulsterman’s retirement. He’s heading into his prime years as a front rower – Best played most of his best [forgiveness, please] rugby in his thirties – and has built up a fair amount of test experience since debuting in February 2017: nine starts and a further eleven appearances off the bench.

With that said, he was never able to launch a sustained challenge to his senior colleague’s grip on the No2 jersey. There’s no shame in that: Best is a bona fide legend of Irish rugby, a Grand Slamming captain with 124 caps, four World Cup squads and two Lions tours to his name. All the same, Scannell has played in 20 tests for Ireland, and has never put in a signature performance to show that he has made his bones at test level. His efforts against Australia in June 2018 were solid and commendable … but so were Herring’s, and Cronin was back on the bench for the win against New Zealand and the opening two games of the Six Nations.

Scannell was an impressive captain of the 2012 Irish U20s, taking on the role in the JWC when Ulster pulled Paddy Jackson from the summer competition. He had a persuasive manner with referees – he gave the appearance that he was really listening intently to them, but was generally able to get his own point across once he had the opportunity. That ability to communicate under stress is not an attribute that many youngsters have, and it’s something that Munster should put an emphasis on bringing to the fore. Munster need more voices and more leaders throughout their team. While admittedly that argument is based on a small sample size, Scannell seemed to thrive with the responsibility before. Instead of waiting around for somebody to give him a leadership role, he needs to make moves to take it. With Best retired and Holland out of the starting line-up in Munster, there’s an opening.

There are about two dozen pictures of Irish forwards getting double-tackled by Japanese players. The symmetry of Matsushima’s and Lafele’s arms here [X marks the spot] and the fact that it’s Cronin being toppled made this an aesthetic and contextual choice. Besides, there aren’t very many photos of Cronin at RWC19; he hardly featured.

- Squads: 2 [May 2019, Sep 2019]

- Age: 33

- RWC19 Games: 2

- RWC19 Starts: 0

- RWC19 Minutes: 41

Cronin only played 41 minutes and was invalided out of the squad before the quarter-final. On the back of a 13-try season for Leinster [in which six of his tries came in European competition, and 5 in interpros], it was a wretched return.

In truth though, Cronin’s test season may as well have ended when he was replaced just after halftime against Italy in February. In a gaff-prone Irish performance, the lineout was only another mis-firing apparatus but the hooker took a full wheelbarrow of criticism from a disgruntled … eh, everybody. He got it in the ear. Brendan Fanning’s article at the time addressed the issue fairly and in depth, but Schmidt took a harder line. He dropped the Leinster hooker out of the next 37-man squad. When you’ve got more than 60 caps and a decade of test rugby behind you, that’s getting dropped from a height. Nobody else got canned, so it looked like the coach had determined that the blame lay with one man.

Cronin’s huge try-count and no less impressive 4.54m/carry over his Leinster season obviously marked him out as a player at the height of his powers, but those are idiosyncratic powers for a hooker. He’s a midfield or blindside line-breaker and a first -rate finisher, rather than a repeat carrier. He’s also a classic ‘tucker’ – not a player who likes to let go of the ball. He’s a negligible threat at the breakdown and his effectiveness as a scrummager have been repeatedly questioned. Fair or not, it’s a doubt that has never gone away.

The idea that a coach ‘can’t get the best out of a player’ is inextricably linked to how the rugby public view the coach; that in turn is inextricably linked to how many wins the coach can deliver. Now that NZ didn’t win the World Cup, Steve Hansen ‘couldn’t get the best out of Rieko Ioane‘ [I’m not even going to mention Akira Ioane]; if he had won it, dropping Rieko for Sevu Reece would have been inspired.

Schmidt probably couldn’t get the best out of Cronin, but no coach can get the best out of every player. Clive Woodward couldn’t get the best out of Simon Shaw, Michael Cheika couldn’t get the best out of Quade Cooper and any number of coaches couldn’t get the best out of RPA 2019 Players’ Player of the Year Danny Cipriani. However, when you’re looking at that sort of situation without emotional ties to the people involved, it’s apparent that it’s always a two way street.

62 of Cronin’s 72 test caps have come off the bench; five of his ten starts came before the 2011 World Cup. His role as a substitute – impact sub, finisher, second captain, whatever – is no doubt frustrating for him but it’s also a natural fit, given the positives and negatives of his playing profile. His subordinate role to Best in the national side was a very complementary pairing, and should have been seen as a partnership as much as a rivalry: Best’s durability, his grinding strength in the tight and his leadership offset by Cronin’s quick feet, irrascibility and nose for the break. Armoured warfare followed by asymmetric warfare, so to speak. Brigadier Toland will like that one.

Herring in action against Australia in June 2018 during Ireland’s series win over the Wallabies. In Best’s absence, his Ulster understudy started the first test and was used off the bench in the other two, performing well in all three games.

Rob Herring

- Squads: 3+1* [May 2019, Sep 2019*, Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 29

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC19 Starts: –

- RWC19 Minutes: –

Herring was called up to replace Sean Cronin in the World Cup squad, following an unfortunate mishap to the Leinster hooker during a recovery session. Herring himself had suffered misfortune right at the start of the run-in to the tournament, forced to hobble off with a back injury midway through the first half of the first warm-up game against Italy in Lansdowne Road.

The South-African born hooker has been an unstinting deputy to Rory Best at Ulster since arriving before the 2012-13 season, playing almost 180 games for the province since then. He hasn’t been handed any unearned rewards. It has been a tough slog for him to get where he is: no underage pedigree, no clubmen alickadoos to promote him on the executive or on committees, no real network of boosters to praise his efforts in the media, either online or on paper. As mentioned in the inset commentary to the chart at the head of this section, he has been very much a fringe contender for international squads for most of his career, more often falling on the wrong side of the selection line than not. His career has progressed in a similar – instructively similar – manner to his long-time Ulster team-mate, Chris Henry.

Henry made his debut as a 24 year old on a summer tour of Australia as an underpowered No8, and then spent a couple of years outside the international jet-set, rebuilding his game as a canny and well-shoed openside. He was returned to the test arena by Declan Kidney as a 28 year old in 2012-13, in recognition of the form that had seen him becoming one of the most frustrating breakdown opponents in European rugby. He was at his prime, both physically and in terms of form for about two years: Kidney’s last year in charge and Schmidt’s first. Then he suffered a serious, non-rugby-related health event, and his prime was done. Like that. He was fit enough to play pro rugby, and there was nothing medically wrong with him, but his performances in 2015 were way off where he had been in the past. He was 31 as opposed to 29 – it’s not a huge age gap – but he just didn’t have it. He was a player who was able to compete at test level when he was at the peak of his career, but once he had passed that peak, he really struggled.

Before anybody metaphorically wades in to berate me for writing down Henry’s abilities, I’m not writing that as a criticism. Recognising a given player’s ability at a given time, and rewarding that ability in a timely manner, should always be amongst a test coach’s priorities. An unfashionable 28-year old might give you a season’s worth of better rugby than an up-and-coming youngster with a big age-grade reputation. Not every player has to be a 60-capper. Not everything is about ‘building’ for a World Cup.

Irish rugby in the last twenty years has predominantly focused on repetitive, or consistent, or conservative selection – choose your adjective according to inclination – and when you look at the comparative records of success pre- and post-2000, it’s difficult to make the argument that it hasn’t been a valid ploy. But of course you can be too conservative [you can be too anything] and many would argue that that has been the predominant trait associated with the downfall of the last three coaches: Schmidt, Kidney and O’Sullivan.

This Covid-19 period has probably come at exactly the wrong time for a couple of players – the 30 year old Dave Kearney is in the form of his life, for example – and I get the feeling that Robbie Herring is one of those unfortunate few. He’ll have turned 30 years old by May, and while that’s not ancient for a front rower, his career to date suggests that, like Henry, he’s a player who has to be at his peak to compete at test level; he just can’t afford to coast or have an off-day.

Ronan Kelleher took immediate advantage of Sean Cronin’s absence at the start of the domestic season, but his repeated selections ahead of well-established backup James Tracey – whom nobody has surpassed in terms of matchday squad selections for Leinster over the last three seasons – makes The Mole believe that Kelleher was going to be given the opportunity to grab the starting spot, no matter who was nominally ahead of him.

Ronan Kelleher

- Squads: 2 [Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 22

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC19 Starts: –

- RWC19 Minutes: –

Ronan Kelleher got an unusual selection push by Leo Cullen at the beginning of the season, being given eight starts in Leinster’s first ten fixtures. That level of repeated selection is not something that has happened very often in the last three years at the province, but he more than repaid his coach’s faith in him … or from an agnostic viewpoint, he validated his coach’s high opinion of his abilities. The 21 year old hooker stormed the early stages of the Pro14, scoring six tries in his first five games, making line-breaks with every other carry and being one of the stand-out forwards on the pitch in practically every game.

It was no surprise that Kelleher was on the up and on his way. The St Michaels College product played in both the 2017 and 2018 editions of the U20 Six Nations, and shone for the Leinster senior team in the warm-up matches at Donnybrook prior to the 2018-19 season. The Mole saw him up close in those games in August 2018, and on the evidence of a couple of halves of rugby there was no doubt in my mind that he was physically ready for the pros at that early juncture of his career. His pace off the mark, tackle height, work-rate and abrasiveness foregrounded him amongst all of the tight-five forwards in Leinster colours.

Kelleher is the least experienced of all the players selected in the senior squad. At the time of his selection for the Six Nations squad, he had just 10 games [9+1 |519 mins] of first grade professional rugby to his name. His youth and lack of experience provides for a couple of readings into his promotion, both as a precocious talent who has forced his way into contention, as well as a coach’s statement of intent with regards to rebuilding at hooker.

Dave Heffernan’s test debut, and his only appearance on the international stage thus far, came against the U.S. Eagles in June 2017. In terms of his build and pace off the mark, the Ballina man has some of the same traits as Sean Cronin, but he doesn’t have them in excelsis like the Leinster hooker.

Dave Heffernan

- Squads: 2 [Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 29

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC19 Starts: –

- RWC19 Minutes: –

Dave Heffernan was a surprise selection in Farrell’s December squad, having not featured for Ireland since a short stint on the June 2017 tour to the US and Japan, when he, by his own admission, didn’t produce his best form. Splitting time through the 2019-20 season in the Connacht No2 jersey with the 34 year old New Zealand-born Tom McCartney [who lead him in terms of starts, minutes played and tries scored], the Mole felt that his inclusion in the stocktake owed something to the unrest at hooker prompted by Best’s retirement, but that it was also a selection based half on egalitarianism [hookers from all four provinces were selected] that would quickly play itself out. And it would play out with Heffernan as the fall guy.

However, it was Niall Scannell who took the dive. The Munster hooker’s startling fall down the depth chart – Farrell obviously doesn’t rate him at this point in time, while many would have seen him as the likely successor to Rory Best – has made it clear that the new boss didn’t always see eye-to-eye with the old boss. The three selected hookers are of a type: bustling, dynamic, fit. There are no real heavyweights amongst them.

The Mole considered Heffernan as a very, very outside contender for a Six Nations berth, but he’s a player who’s easy to like, easy to cheer for. His fierce workrate, quickness off the blocks and assured handling make him very visible across the field, and he has come into contention with very little hype on his side. He’s had to work hard for a long time to get his shot. How he will fare in the tight against some of the huge beasts he’ll encounter at test level is a cause for concern, however.

In Summation: Hookers

Frankly speaking, at this point in time Ireland’s depth at hooker is at its lowest ebb in a quarter of a century. Now, Ireland have been well served by hookers in that period. The RWC95 squad was captained from hooker by Dolphin’s Terry Kingston, who was playing in his third World Cup; his back-up was a then-23 year old Keith Wood.

Wood’s storied career saw him captain Ireland; win a test series with the Lions in South Africa, and compete four years later in an epic series against the world champion Wallabies; win the inaugural IRB International Player of the Year award in 2001; score more test tries than any front-five forward in international rugby [at the time of his retirement]; and earn a reputation as one of the greatest hookers to have played the game.

While nobody could fill the gap that he left, Shane Byrne stepped up and did a manful and under-appreciated job. Munch started the first and last tests for the Lions in New Zealand in 2005, and played in the second off the bench; for three Lions tours in a row [South Africa in 1997, Australia in 2001 and New Zealand in 2005], Ireland provided the starting test hooker in seven of nine test matches. The Mole would hold that there hasn’t been a more overlooked Irish test Lion in the professional era than Byrne. The then 34-year old Aughrim man played his last test for Ireland in November 2005, replaced piecemeal by the fierce Flannery/Best rivalry. When injuries plagued the second half of the Munster hooker’s career, the Best/Cronin tandem emerged as a prototypical slogger/springer combination for the best part of a decade. Along the way Frankie Sheahan, Richardt Strauss and Damien Varley pushed their way into the international mix and World Cup squads with combative, gritty and skilful performances for their provinces over multiple seasons. These guys were veterans when they won their call-ups, and they were fighting for scraps.

In comparison, the present-day cupboard is bare. There’s a prospect [Kelleher], a journeyman [Herring], a mired, unfulfilled talent [Scannell] and a wild West Rudy who’s going at 100mph just to keep up [Heffernan]. The position is is wide open, but the postponement of the season has left unfulfilled any hope for the emergence of a definitive, evidence-based depth chart.

Tighthead

Curiously, the No3 jersey has begun to look like a position of real strength for Ireland, despite a noticeable fall-off in form of the current holder. Three highly rated players in their early-to-mid twenties fill the depth chart, with ideal spacing in terms of age profile.

There’s distance between the top two and everyone else. The distance between those two isn’t as wide as it had been previously, however.

Furlong’s inconsistency swung both ways: he had his moments, too. The big Wexford tighthead scored a couple of tries in the tournament, and his three since his seasonal debut in mid-August makes him one of Ireland’s most prolific target men; only Andrew Conway has a better strike rate over that period. But his overall form showed a real decline from his previously high standard and the World Cup was a disappointing tournament for him.

Tadhg Furlong

- Squads: 4 [May 2019, Sep 2019, Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 27

- RWC19 Games: 5

- RWC19 Starts: 4

- RWC19 Minutes: 230 [12th]

The Wexford tighthead’s World Cup was arrhythmic and disappointing. Given the standards he has previously set, he was one of Ireland’s most significant underperformers.

It’d be unfair to characterise Furlong’s tournament as a complete disaster. He togged out in all five games, started in four, had a reasonable outing in the comprehensive win over Scotland, and showed some of his jukebox form against Samoa, ending a showreel run with a well-earned touchdown. On the other hand, his performance against Japan was littered with errors of all kinds, and his tournament ended on a bum note when he had one of the worst performances of his career in the quarter-final against the All Blacks. While the scrum was stable – any tighthead’s purview – he was embarrassed in the loose. Joe Moody, his direct opponent on the night, ran through him twice.

The bad showing against New Zealand was somewhat camouflaged by the litany of mistakes made by other players; if a turd falls in a sewer and nobody hears it splash, does it stink? However, Ireland weren’t as inept against Japan – apart from Furlong. He was entirely out of sorts. Knock-ons in contact, knock-ons out of contact, soak tackles, passes thrown to the ground, chronic struggles against his opposite number in the scrum, ball-watching at the back of a ruck … it was a poor showing by any standard of test rugby, desperately poor by the standards he has set himself. He was substituted off at 46′ for Porter, subbed back on at 55′ and then subbed back off after the Japanese try, three or four minutes later.

The Irish front row were roundly outplayed by their opponents: out-run, out-passed, and out-tackled. But while his colleagues were merely outplayed on the night, Furlong actively had a ‘mare. I was one of the two Moles at the game, and didn’t realise that Furlong had come back on during the second half [after Schmidt subbed him off for Porter, which must have been a HIA] until I watched a recording of it back in Ireland. Cue hands over eyes.

On form, Furlong is an outstanding player who can genuinely lay claim to being world class: he’s one of the best three players in the world in his position. There was a two year period [2017-18] when he was unanimously acclaimed as the best tighthead in the world, but Kyle Sinckler’s performances over 2019 have certainly put the Englishman into pole position. That Furlong’s stock has slipped is irrefutable. Like Sexton and Murray, other key players for the Lions in 2017 who shone for Ireland in 2018, he wasn’t able to maintain the levels of performance that Irish fans have grown to expect.

Whether he was carrying a niggle and was trying to manage himself through the tournament until the knockouts, has let his focus slip, or was simply weighed down by the same malaise that overtook so many of his teammates in 2019, Furlong’s performances were unfortunately very scratchy. His reputation, widespread popularity and relative youth – this was his first poor run of games, and people aren’t tired of him yet – shouldn’t mask what was a poor tournament.

The Mole feels that Andrew Porter is an under-appreciated player, and that what he has done in changing from an age-grade loosehead to a test tighthead in two years is significantly undervalued.

Andrew Porter

- Squads: 4 [May 2019, Sep 2019, Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 24

- RWC19 Games: 5

- RWC19 Starts: 0

- RWC19 Minutes: 134 [21st]

Porter was one of nine players to feature in all five games of Ireland’s World Cup expedition, and the only one of that nonet not to be given a start. He’s used to that score: 19 of his 23 test caps thus far have come off the bench. As a result, he has a lower public profile than his age-grade colleagues James Ryan and Jacob Stockdale. He tends to be forgotten, or at least not really afforded the same level of recognition.

Tadgh Furlong is generally accepted as being amongst the top two or three tightheads in world rugby, and that Porter is his back-up not just for Ireland but for Leinster as well means that there’s not a vocal provincial fanbase extolling his claims for a starting spot. Furlong gives a great interview, and his quick wit and farming background have made him a fan favourite across the country.

In contrast, Porter is a more introspective character, not particularly partial to public attention or given to small talk and meaningless back-and-forth. His tattoos are pretty idiosyncratic for an Irish rugby player, particularly one who graduated from St Andrew’s College, Booterstown. In strict rugby terms, his move to tighthead has meant that his emphasis over the last two years has been on the grinding work of the scrum, rather than the bustling runs that characterised his two years at loosehead on the Irish U20s side.

However, Porter’s progress has been exceptionally good. He’s accumulated more caps than Furlong had at the equivalent age, and that period has incorporated changing position as well. Furthermore, he accomplished the switch from loosehead to tight over a short timeline with the minimum of fuss. Porter has always been generous in praising the help he has got from coaches and his fellow props at Leinster, but he’s the one who has done the work and made it happen. It’s an incredibly difficult switch to make; Porter likened it to learning to write with your other hand.

Tightheads make considerably more money than looseheads in every league in Europe so unless you’re a superstar loosehead who can command a salary that outstrips his position, there’s a huge incentive to make the switch to the other side of the scrum. Very few make the move, because it’s so difficult to do and there’s no guarantee that it will take.

Beyond the scrummaging work, his abilities as a jackal have grown to mitigate the slide in his ball carrying. This change in style largely fits in with the tighthead’s role; Dan Cole was another great breakdown exponent in the middle of his career. Porter won the second highest number of turnovers at the breakdown at Leinster in the 2018-19 season, behind only Scott Fardy. He’s incredibly difficult to get off the ball.

On The 42’s excellent Rugby Weekly podcast, Andy Dunne was pretty insistent that Porter was an iffy choice for the No18 shirt. The Mole agreed with the principle, but not the terms: John Ryan’s form wasn’t pushing Porter for the sub-tighthead spot, Porter’s was pushing a wobbly Furlong for the starting spot.

John Ryan helps to drive Ruddock over the Russian line for a try. There’s a Russian player hidden somewhere underneath them too, flattened. This was Ryan’s only selection of the tournament.

John Ryan

- Squads: 2 [May 2019, Sep 2019]

- Age: 31

- RWC19 Games: 1

- RWC19 Starts: 1

- RWC19 Minutes: 58 [30th]

From well over a year out it was obvious that Ireland were stronger and deeper at loosehead than they were at tighthead: Kilcoyne’s performances had picked up to the point where he was giving Jack McGrath a hard run for the No17 jersey, and Cian Healy was playing as well as he had ever done in a decade of test rugby. The Clontarf man had won 88 Irish caps by the end of the 2018-19 season, and McGrath had 54 to his name by the same deadline. Kilcoyne debuted in 2012 – the season before McGrath – and had won 29 caps before making his first appearance of the 2019-20 season against Wales in Cardiff in late August. In contrast, Furlong had won 33 Irish caps [22+9] since his debut in 2015, Ryan 18 [14+4] since his first call-up in November 2016, and Porter 14 [3+11] since his introduction in June 2017.

Your third choice prop is always going to be on the verge of irrelevance in a 31-man RWC squad. They’re back-up to a back-up, an emergency device. Since the squad size was expanded to 31 in the aftermath of RWC 2011, almost all coaches have opted to bring five props: the assumed norm has been to select three tightheads and two looseheads rather than vice versa, on the basis that tighthead is a more difficult scrummaging task.

Ryan has played on both sides of the scrum, although his last starts for Munster at loosehead were back in the 2014-15 season. Porter ended up covering loosehead against Russia, giving Cian Healy [the oldest prop in the squad] a valuable breather. More significantly, the St Andrews College man was selected at No18 in every other game. Whenever there was a choice between Ryan and Porter uncomplicated by other selections, Porter got the nod. The only agenda there was achieving success: if Feek, Easterby and Schmidt thought Ryan was a better bet, then they would have selected him.

It was telling that Ryan only went 57 minutes against Russia. Furlong had played 54 minutes against Japan in humid conditions five days previously, but with the game bogged down in the morass that was the third quarter and Ireland no closer to a vital fourth try against a 14-man Russia, Schmidt made the necessary call to bring him on. Furlong had started the first two games [and would go on to play in all five games], Porter would go on to play in all five, and Ryan was making his first – and, as it turned out, his only – appearance in the tournament. The obvious call would be to send the Corkonian the distance, to push him for 80 minutes and let Furlong sit this one out. However, the Irish pack was having a hard time against the Russians, with no evidence that they were going to wrest back momentum. Within four minutes of the introduction of Porter, Cronin and Furlong, Conway had bagged the fourth five-pointer and the job was in the bag.

Ryan worked hard to get in the squad, and his so-so performance against Russia didn’t have that big an impact: Ireland got their bonus point, Furlong didn’t get injured and went out the following week to have a stormer against Samoa. At the same time, he didn’t provide any real options to the coaching squad. They only picked him in one match-day squad, and that was against the whipping boys of the group.

Bealham’s finest hour came in Soldier Field in November 2016, Ireland’s first win over the the All Blacks in test competition. He was a Joe Schmidt favourite that winter, but the page turned the following year when Connacht’s form collapsed, Pat Lam left and the magic disappeared.

Finlay Bealham

- Squads: 1 [May 2019]

- Age: 28

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC19 Starts: –

- RWC19 Minutes: –

Robust and abrasive, the Australian-born Connacht prop was a member of Schmidt’s 45-strong training squad, but one of the unfortunate trio [himself, John Cooney and Mike Haley] to be dispensed with at the second cut. Bealham had featured for Ireland as recently as the November 2018 internationals, after an 18-month long absence from the test arena; thus his presence in the training squad, while a little surprising, was not a complete shock. The Mole is certain that it stemmed from two sources: his ability to play both sides of the scrum, and his excellent form in 2016, where he featured for Schmidt in wins over New Zealand and Australia, and a tight loss against South Africa.

Bealham was a classic Schmidt find; the New Zealander picked him out, coached him up, and while he might have worried about putting him in to do a job against some of the best teams in world rugby – sure he worried about everything! – he had the courage of his convictions. And you’ve got to say that his confidence was repaid.

There’s every chance that Bealham mightn’t fit the mould that Farrell or Fogarty are looking for in a tighthead, and the indications – namely his omission from the new head coach’s first two squads – are that he doesn’t. But he’ll always have Chicago.

Marty Moore’s last appearance for Ireland was in the Championship sealing victory over Scotland in Murrayfield in the 2015 Six Nations, more than five years ago.

Marty Moore

- Squads: 1 [Dec 2019]

- Age: 29

- RWC19 Games: –

- RWC Starts: –

- RWC Minutes: –

Marty Moore won two Six Nations medals under Joe Schmidt, featuring in all ten games of the 2014 and 2015 tournaments as Mike Ross’ understudy. He has an 80% win rate at test level, and he played all his international rugby in two Six Nations tournaments, both of which he won. In terms of efficiency, it’s an amazing record. The fact that he accomplished those feats by the time he turned 24 and hasn’t played a single minute of test rugby since is a sign that his career took a serious wrong turn.

His beginnings in test rugby were equally abrupt. Schmidt gave him his Leinster debut as a first year academy player in April 2012, and gave him another selection push the following season. The New Zealander was quick to call him into service early in 2014 after trying out Declan Fitzpatrick and Stephen Archer in the November 2013 series.

Moore’s decision to exit IRFU employment and sign for Wasps may not have been a career-killer, but it certainly was a career-crippler. It came against the background of an injury-disrupted 2014-15 season which saw in-season surgeries on both shoulders, followed by a pre-season broken metatarsal which meant he was unavailable for selection for RWC15. The unstoppable rise of Tadhg Furlong during those injury-enforced absences probably put some doubts in his mind over his place in the national shake-up, but his move to Wasps seems to have been little short of a disaster.

Ulster offered a way out after two years of a three-year contract, but Schmidt wasn’t interested in extending the olive branch. The tighthead didn’t feature in any of the coach’s squads through the 2018-19 season, and an ankle injury in April put paid to any slight chance he might have had of featuring in the 45-man training squad. Moore’s fitness and physical preparation have always weighed against his undoubted scrummaging prowess and his strong rugby instincts – he’s an excellent tackler and a very strong jackal over the ball – and it is an issue that hasn’t gone away. And The Mole expects that Moore’s conditioning will stand against him in Farrell’s eyes too. When Farrell turned pro for Wigan in 1991 – as a 16 year old – the northern code was about a decade ahead of union in terms of strength and conditioning; all the coach knows is professionalism, mental resilience and hard work. It was drilled into him as a teenager. Scrummaging is a lost art in rugby league, and the rookie head coach won’t have any feather-brained childhood remembrances of fat props trailing the play around and catching up when the ball has gone dead.

While not having to return quite to the bottom of the pile, Moore’s decision to throw in his lot with Wasps, and his failure to thrive there, meant that the middle three years of his career were a wash-out. He failed to register any major on-field accomplishments, and wasted the momentum of his outstanding start to test rugby. But everybody makes bad decisions; it’s part of the human condition. That he’s back playing regularly and back around the fringes of a squad under a new Irish coach is a welcome return.

Tom O’Toole

Big Tom and the Gainliners! Anytime Ireland call up a forward called Tom, that caption comes into play. O’Toole replaces Court in the titular role.

- Squads: 2 [Dec 2019, Jan 2020]

- Age: 21

- RWC19 Games: –

- Starts: –

- Minutes: –

The 21 year old Tom O’Toole played in all 18 of Ulster’s games thus far this season, quickly building on the 18 appearances he made last season. Born in Drogheda, raised in Australia and schooled in Campbell College, it has been revelatory to see how quickly he has become an integral part of Ulster’s pack. Ulster have had huge issues over the last decade translating academy forwards into the senior squad, but O’Toole has strolled through. Coach Dan McFarland was a prop as a player, and his first twelve months at Ravenhill have seen him lay a rock solid front row as the foundation for his ongoing efforts. Marty Moore was recruited from Wasps, while Templeogue’s Eric O’Sullivan was coached, backed and selected to hit performance heights of which few had previously thought him capable. 56-times capped Irish international Jack McGrath was tempted north from Leinster. O’Toole, the youngest of the group, was pushed to contribute directly off the back of his performances for the Irish U20s in the 2018 Junior Six Nations.

MacFarland’s ability to build a strong propping corps in a very limited amount of time has not only made Ulster a genuine contender in two tournaments, but it has also provided those players with a base from which to stake a claim for test recognition. O’Sullivan was always going to suffer a drop in gametime with McGrath’s arrival [he made 18 starts last season and a further eight as a substitute], and his profile has dipped as a result, but O’Toole’s two-man show with Marty Moore hasn’t affected his international claims. He benefits from the stylistic contrast to Moore; the latter is an old-fashioned tighthead, stumpy and wide, whereas O’Toole is a physical specimen straight out of the box.

A full decade younger than John Ryan, the third tighthead in the Schmidt’s World Cup squad, O’Toole’s selection looks like a call that Farrell has made with one eye on the future. O’Toole is probably not quite at Ryan’s or Moore’s level as a scrummager in 2020 – alright, I’ve written ‘probably’ when I could just as easily say he’s not – but his physical limits are set at a higher point than either: if you put them in a variety of physical tests against each other that took in running, jumping, pushing and pulling, I’d put cash on the barrelhead that O’Toole would finish the day on top of the pile. Outside of athletic ability, his competitive edge on the pitch is obvious. He’s got an identifiably abrasive on-pitch nature, the streak of toughness that you need as a top quality forward. Farrell likely sees in him the potential to thrive at test level, and wants to get the learning process started as soon as possible.

In Summation: Tightheads

Of all the front row positions, Farrell will be happiest with his stocks at tighthead. He’s on his f*cking uppers at hooker for one thing, and his looseheads are probably a little too old and a little too tightly grouped age-wise to be optimal.

In contrast, there’s a text-book three-year spacing between his top-three tightheads, and all of them are in their 20s. Their age means that a season lost to pandemic quarantine will be a season added to the other end of their career; it’s just not the same for guys in their early-to-mid 30s. However, there are a couple of issues on the horizon that cast a shadow on an otherwise sunlit prospect.

Furlong’s form was a worry before the hiatus. He showed a good competitive attitude to bite back when dropped in favour of Andrew Porter for a couple of Leinster’s Heineken Cup games, but his last match against England was a return to the worst of his 2019 form. The Wexford man is still a shoo-in for a Lions tour that is now closer than ever, based on his 2017 and 2018 form alone. When I say that the tour is closer than ever, it’s not that the dates have changed, but that there will be many, many fewer matches than originally scheduled between now and when that the squad is announced. Lions tours make legends but damage careers.

A curious question mark hangs over Andrew Porter’s future. His history as an outstanding age-grade loosehead, the age profile of the current loosehead corps and his particularly strong form are prompting calls for his return to the left hand side of the scrum. Switching back to loosehead would likely be easier than switching across to tighthead, but just because Porter has made playing test tighthead at test level as a 22 years old look achievable doesn’t make it achievable for anybody else. Ernie’s young fellah is a physical phenomenon steeped in rugby since childhood. That’s a question that won’t be immediately addressed, but is worth a long term ponder down on the Ponderosa.

As ever, a wonderful piece of writing, thinly disguised as an erudite rugby analysis. Welcome back to the Demented Mole. The Pandemic has produced a ray of sunshine.

Great work, can’t wait for the next installments!

Really outstanding stuff and I was dying to finish up the day job to get to read it. One ask though, the sidebar Shota Horie was really the most impressive part. Can you do that for each position as you go through the rest of the positions? What does a world class player in this position look like and what does our current crop of players need to do to get there as the final piece? It would be great to do in the guise of what is possible for an Irish player looking to win a RWC (ie we are not ever going to bred a South African styled pack that can dominate physically). In short, for a hooker we need a Rory Best scrummager, Jerry Flannery Line out thrower, Rory Best in his late 20’s to jackal in open pay and Sean Cronin ball carrier in the open….

Re: Rory Best, while his lineout stats were commendable in the 2019 World Cup after the chastening warm-up defeat in Twickenham against England, the numbers do not tell the full story. The lineout throwing selection was incredibly conservative: 2 position and 4 position options in a full lineout and shortened lineouts. While it helped secure our own ball (due to his career weakness at throwing), it hugely impacted the backline for taking it to our opponents in first phase by never getting the premium off the top ball from the tail of the lineout ball. The was a second order impact of a team going back into its shell and being conservative in all facets.

A great article. With McCartney now retiring at Connacht it will put Heffernan in the drivers seat to get more gametime next season which might drive him on to newer heights. What do think about Delahunt mole? He was always well regarded but his form seems to have slipped this season.

As for Bealham I think it was a mistake to leave him out of the RWC squad. I can understand why but with Bealham’s all round game better than Ryan my thinking was Bealham could do the same types of play like Cronin did for Ireland. Shame.

Superb read as always, thanks for the efforts. Looking forward to the next set of installments